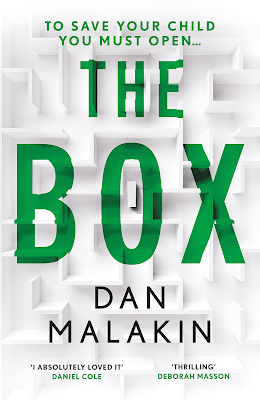

Many moons ago I spent a few days with Dan Malakin on a writing course so I’ve long known him to be an all-round good guy and a damned good writer. Clearly, though, he’s spent the intervening years honing his writing craft because he’s an even better writer now than he was then. That much was clear with his first novel, The Regret, which told the story of Rachel, whose life unravelled at the hands of a computer hacker. Re-reading my review of that novel, one of the things that struck me at the time was how beautifully paced it was. But, I noted:

The Regret does indeed rattle along at pace, but importantly this is not to the detriment of character or emotion. Where many novels eschew character building in their headlong impulse to thrash the story along, The Regret draws us expertly into the troubled mind of the protagonist Rachel, a woman who has suffered trauma in her life and is now, forcibly, having it revisited on her.

Well, damn me, that’s precisely the point I was going to make about The Box...

The story: Ally Truman, a young woman, is being targeted by a right wing incel organisation, Men Together. Her family house is being picketed by organisation members. Her father, Ed, is accused of sexual assault. Her brother is largely estranged from Ed, and Ed fears his family is falling to pieces.

Then Ally disappears.

And so is set in motion a narrative that never lets up. Ed is convinced Ally has been abducted but, before he can contact the police, he finds himself the key suspect in a murder, after his DNA is found on a murdered young woman’s body. He flees, teaming up with a friend of Ally and this unlikely pairing go on the run, determined to find out what has happened to Ally.

What has happened? Why? How? And, most importantly, who do we believe?

What unfolds is a tightly wound and terrifying tale, leading to a brutal and unexpected denouement. The Box is a masterclass of thriller writing, tense and taut, unpredictable, utterly compelling.

But.

Back to my review of The Regret, and my observation that Dan Malakin takes care to draw credible and appealing characters. Dan doesn’t write plot-by-numbers. His characters do not react to events as they must in order to impel the story, but as they would according to their natures.

What is most impressive about The Box is not the pace and intensity of the narrative, it is the fact that, despite the driving rhythm of the novel, Dan Malakin still manages to draw out some important messages about contemporary society. This is a timely novel, engaging with the eerie world of right wing incels, that shady group of misfits and malcontents for whom misogyny is a way of life and whose increasingly violent, indeed deranged, views on women are growing ever more sinister. Malakin takes us into the heart of that group, confronts head-on this evil intent masquerading as political activism.

But he never does this in any didactic way and, although we are informed clearly about the nature of these groups, such descriptions never detract from the plot or slow it down or cause any longeurs. Believe me, writing this tight takes a lot of effort.

The Box is an exhilarating

journey, a journey into the darkness of people’s minds and the implacability of

hope. This is fiction to savour.