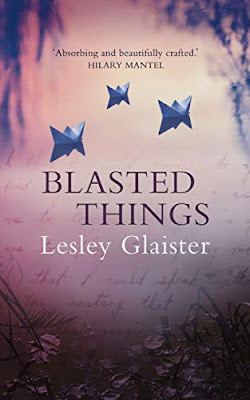

I remember buying and reading Lesley Glaister’s early works when I was a stock librarian in the nineties. As is often the case, I was initially attracted by the covers (Digging to Australia, I think, had a Paula Rego painting and that was my introduction to her) and I found Glaister’s writing immersive and intriguing. When I stopped being a librarian I read less and lost touch with Lesley Glaister until Blasted Things, published by Sandstone Press. I’m delighted to have re-made her acquaintance.

The first section of the novel is set in a field station on the Western Front during World War One in 1917. Clementina Armstrong – Clem – is an auxiliary volunteer nurse and we begin to understand that an interesting back story has led this young woman to such a difficult and dangerous assignment. She is engaged to be married to a doctor but already has doubts – not so much about her fiance Dennis but about marriage itself, the institution, the life that awaits a young woman in Edwardian England. Her experiences in the casualty station, the young men who pass through her care – some surviving, many not – reinforce her doubts.

And then she meets Powell Bonneville, a Canadian doctor, and those doubts, doubts which she has tried to hide deep in her psyche erupt into the open.

Life turns. War over, we rejoin Clem in 1920, now married to Dennis, with a son and a new life and the bright future that everyone in Britain, fatigued by war and death, aspires to have. This was a peculiar time, euphoria and relief and hope in the immediate aftermath of the war not yet eclipsed by the inevitable recession and social crises that would follow later in the decade.

For Clem, this transition from hope to gloom comes early and bites hard. Those doubts she harboured have never gone away, and a combination of post-natal depression, (obviously undiagnosed) PTSD from her experiences at the front and the growing realisation that her life was, indeed, to be girdled by convention leave her morose and marooned, her life circumscribed: more children would follow, the doctor and his little lady becoming pillars of the community, she on his hand, smiling, projecting radiance through her slow descent into middle age and on, the inevitable arrival of grandchildren, infirmity, decline.

Only Dennis’s sister, the free spirit Harri, seems to offer any escape from the stultification of Edwardian society. Harri’s husband died in the war and, despite Dennis’s attempts to have her return to the family bosom, she steadfastly retains her own household and, through that, her own identity. Returning from Harri’s to the family home is a stinging experience for Clem, a reminder of what she had hoped her life might encompass.

In this state of mental turmoil she meets Vincent, a man badly disfigured during the war, with a tin plate hiding the damage to his face. A brittle relationship develops, and here the novel twists into remarkable new territory, these damaged and yearning characters, in most regards utterly mis-matched but each recognising in the other some deep-rooted need, coming to life before us on the page. As a character study it is remarkable, beautifully handled, the pair’s arguments and misconceptions and overreactions rendered all too human through the realism of their depiction.

This section of the novel reminded me strongly of Patrick Hamilton’s Hangover Square, set in 1939, immediately before the war. Like Blasted Things, it is an intriguing character study based around unhappy and needy and disconnected people. There is in it an underlying sense of decay – social and moral – which is only hinted at in Blasted Things. The trajectory is clear, then: from 1920s Blasted Things to Hangover Square in 1939, this is how British society is going to develop, this is where we are headed. Hamilton had the advantage of writing his novel almost contemporaneously, of course, reflecting the zeitgeist around him. Glaister’s ability to enter the psyche of the fractured 1920s is impressive indeed.

In an interview, Glaister said of her work: “It doesn’t really fit into any genre. Is it historical? Is it a romance? Is it a psychological thriller?’

She wondered if this might somehow be a problem but for me the opposite is true: it is a strength. The novel twists the way it chooses and Glaister, the author, follows. It could have gone in a particular direction during and after the first section, in the field hospital. It didn’t. It defied convention and became something different. Difference continues throughout the novel. Nothing is predictable. Nothing is straightforward. The novel becomes more than the sum of its parts, a vivid evocation of time and period, emotion and character.