Here is a fine piece of descriptive writing from One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest by Ken Kesey.

I realised I still had my eyes shut. I had shut them when I put my face to the screen, like I was scared to look outside. Now I had to open them. I looked out the window and saw for the first time how the hospital was out in the country. The moon was low in the sky over the pastureland: the face of it was scarred and scuffed where it had just torn up out of the snarl of scrub oak and madrone trees on the horizon. The stars up close to the moon were pale; they got brighter and braver the farther they got out of the circle of light ruled by the giant moon. It called to mind how I noticed the exact same thing when I was off on a hunt with Papa and the uncles and I lay rolled in blankets Grandma had woven, lying off a piece from where the men hunkered around the fire as they passed a quart jar of cacturs liquor in a silent circle. I watched that big Oregon prairie moon above me put all the stars around it to shame. I kept awake watching, to see if the moon ever got dimmer or if the stars got brighter, till the dew commenced to drift onto my cheeks and I had to pull a blanket over my head.

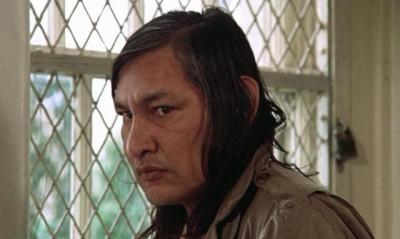

As an example of how to integrate descriptive writing into narrative, this cannot be beaten. The narrator is Chief Bromden, an inmate in an asylum who is doubly cloistered by the perception in his head that the world is under the control of ‘The Combine’, which controls thoughts and actions in secrecy. Not long before this passage, there is a harrowing scene in which the Chief describes the impenetrable fog which he thinks The Combine brings down on the world in order to go about its business. This, then, is a man wholly confined. And yet, of course, he is a countryman, used to freedom and open spaces. It is a tragic situation he has found himself in.

And so, in this passage, we get the first inkling of the Chief looking outward once more. He notices for the first time the rural location of the hospital and gives a vivid description of it. This seamlessly leads him into a reminiscence of a happy experience from his childhood. The shift is beautifully handled – a moment of relaxation in the present, releasing repressed memories of the past. In this way, description of landscape is being used specifically to build character and character development. It is beautifully handled.

The passage continues, and it is worth quoting at length because it is superbly done:

Something moved on the grounds down beneath my window – cast a long spider of shadow out across the grass as it ran out of sight behind a hedge. When it ran back to where I could get a better look, I saw it was a dog, a young, gangly mongrel slipped off from home to find out about things went on after dark. He was sniffing digger squirrel holes, not with a notion to go digging after one but just to get an idea what they were up to at this hour. He’d run his muzzle down a hole, butt up in the air and tail going, then dash off to another. The moon glistened around him on the wet grass, and when he ran he left tracks like dabs of dark paint spattered across the blue shine of the lawn. Galloping from one particularly interesting hole to the next, he became so took with what was coming off – the moon up there, the night, the breeze full of smells so wild makes a young boy drunk – that he had to lie down on his back and roll. He twisted and thrashed around like a fish, back bowed and belly up, and when he got to his feet and shook himself a spray came off him in the moon like silver scales.

He sniffed all the holes over

again one quick one, to get the smells down good, then suddenly froze still

with one paw lifted and his head tilted, listening. I listened too, but I

couldn’t hear anything except the popping of the window shade. I listened for a

long time. Then, from a long way off, I heard a high, laughing gabble, faint

and coming closer. Canada honkers going south for the winter. I remembered all

the hunting and belly-crawling I’d ever done trying to kill a honker, and that

I never got one.

I tried to look where the dog

was looking to see if I could find the flock, but it was too dark. The honking

came closer and closer till it seemed like they must be flying right through

the dorm, right over my head. Then they crossed the moon – a black, weaving necklace,

drawn into a V by that lead goose. For an instant that lead goose was right in

the centre of that circle, bigger than the others, a black cross opening and

closing, then he pulled his V out of sight into the sky once more.

I listened to them fade away

till all I could hear was my memory of the sound. The dog could still hear them

a long time after me. He was still standing with his paw up; he hadn’t moved or

barked when they flew over. When he couldn’t hear them any more either, he

commenced to lope off in the direction they had gone, towards the highway,

loping steady and solemn like he had an appointment. I held my breath and I

could hear the flap of his big paws on the grass as he loped: then I could hear

a car speed up out of a turn. The headlights loomed over the rise and peered

ahead down the highway. I watched the dog and the car making for the same spot

of pavement.

The dog was almost to the rail

fence at the edge of the grounds when I felt somebody slip up behind me. Two people.

I didn’t turn, but I knew it was the black boy named Geever and the nurse with

the birthmark and the crucifix. I heard a whir of fear start up in my head. The

black boy took my arm and pulled me round. ‘I’ll get ‘im,’ he says.

‘It’s chilly at the window

there, Mr Bromden,’ the nurse tells me. ‘Don’t you think we’d better climb back

into our nice toasty bed?’

‘He cain’t hear,’ the black boy

tells her. ‘I’ll take him. He’s always untying his sheet and roaming ‘round.’

There is an astonishing poignancy to this. We have this man, physically trapped in an asylum and mentally enclosed by his own irrational fears, and it is counterpointed by, firstly, the flighty dog, then the skein of geese and finally by a car – all of them free, going about their own business unhindered. Meanwhile, the Chief describes all of this in exquisite detail – ‘blue shine of the lawn’, the ‘black, weaving necklace’ of geese, the steady and solemn lope of the dog. Be clear, whatever the Chief’s current situation, here is a man at ease with nature.

And then the reality, perhaps portended by the arrival of that car – humanity, modern progress – and the Chief becomes aware of a presence behind him. The ‘whir of fear’ starts up in his head. His reverie is over, his moment of freedom finished. The black boy and the nurse deal with him gently enough, but consider the nurse’s words, her patronising use of the first person plural, the childish description of a ‘toasty bed’. This to a man who could conjure such magical descriptions, who demonstrates a remarkable sensitivity to nature, but the nurse blithely assumes that there is nothing happening in his brain, that he is some sort of zombie wandering the ward aimlessly and staring vacantly into space. And the scene concludes chillingly, with that reminder of the Chief’s situation, the sheet that has to be tied around him nightly to confine him to his bed. It is clear that the Chief may have found a solitary, fleeting moment of escape, but it was a chimera. He is unable to comprehend our world. But we, to our shame, are equally unable to comprehend his. A more poignant description of mental illness it would be hard to find.