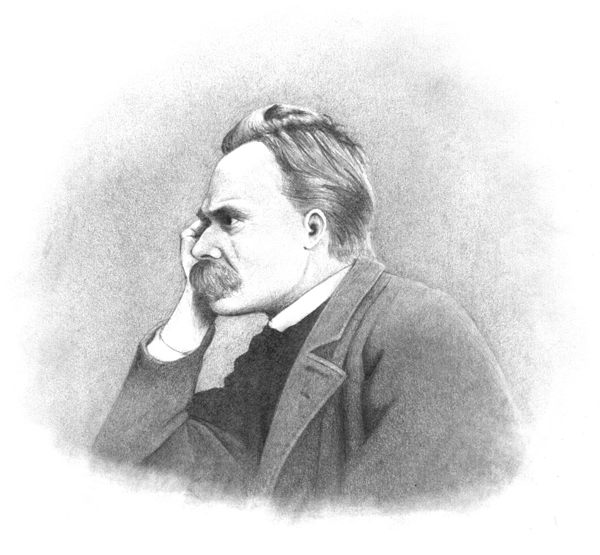

The connection between the work of Cormac McCarthy and

Nietzsche’s Thus Spake Zarathustra is frequently made, most often in

connection with Blood Meridian. The Road, too, could be read in a

Nietzschean light, and it has been suggested that its opening, when the man

wakes in ‘the dark and cold’ is emblematic of the eternal return. Maybe so, but

if it is, it is not Nietzsche’s eternal return that McCarthy is describing. The

first thing to note about Nietzsche’s eternal return is that it isn’t

necessarily meant literally. Nietzsche was much more playful than he is given

credit for. The second thing to note is that, as regards the soul, Nietzsche

doesn’t necessarily agree that it is a separate entity. And he doesn’t go along

with the notion that – as a separate entity – it is reborn. Zarathustra tells

us: ‘Only where there are tombs are there resurrections’. The first mention of

soul in Thus Spake Zarathustra, linking it to God and the ‘poisoners’

who ‘speak of superearthly hope’, describes it pejoratively:

Once the soul looked

contemptuously on the body, and then that contempt was the supreme thing: the

soul wished the body meagre, ghastly, and famished. Thus it thought to escape

from the body and the earth.

This is not to say that Nietzsche does not accept the idea

of the soul – he plainly does, as it reappears throughout Zarathustra, but he

does not seek to place it on a pedestal. On the contrary:

Oh, that soul was itself meagre,

ghastly, and famished; and cruelty was the delight of that soul!

But ye, also, my brethren, tell

me: What doth your body say about your soul? Is your soul not poverty and

pollution and wretched self-complacency?

Of what is this soul comprised? In Nietzschean terms it is

only part of the body. Zarathustra tells us:

“Body am I, and soul” - so saith

the child. And why should one not speak like children?

But the awakened one, the knowing

one, saith: “Body am I entirely, and nothing more; and soul is only the name of

something in the body.”

The soul, then, is a part of the individual, and could be

construed as the state of overgoing wisdom. In this, there may be some

connection with the idea of eternal return, in as much as this concept is key

to understanding Nietzsche’s idea of the progress of man from herd to overman.

For Nietzsche, eternal return is a way of reconciling oneself with the past.

The overman can only be attained if one learns to love life completely, such

that the idea of eternally returning to each moment bcomes acceptable. This is

a troublesome concept, of course, in moral terms, because it entails final

acceptance (though not approval) of events such as, say, 9/11 or a murder of a

close relative and so on. People therefore tend to get stuck on the concept of

eternal return here, but again I stress that I don’t think Nietzsche is being

literal: it is not the event, but one’s connection with it and understanding of

it that matters. It is rooted in the love of the present, the here and now.

Through understanding the past, accommodating it, reconciling onself to it,

removing all anger and resentment and negative emotion from our understanding

of it, we allow ourselves to live more fruitfully in the present. We find

redemption, in other words, because redemption comes from ourselves and our

connection with the world, not from a god who, at the end of a life, graciously

bestows it on the worthy. By accepting the past we affirm the present. We feel

no need to prepare ourselves for the great redemption of the end. John Updike,

in one of his last poems, Peggy Lutz, Fred Muth, nails this beautifully,

when he writes:

To think of you brings tears less

caustic

than those the thought of death

brings. Perhaps

we meet our heaven at the start

and not

the end of life.

Now, it may be that I am falling prey to my usual kindly,

naïve humanist perspective here. Nietzsche was more definite. He said: ‘To

redeem the past and to transform every ‘It was’ into an ‘I willed it thus!’ –

that alone do I call redemption!’ Again, taking the 9/11 or murder examples, it

is possible to reach the point I suggest – understanding, reconciliation – without too much difficulty, but to reach the

Nietzschean moment of ‘I willed it’ is more of a struggle. But he goes on: ‘The

will cannot will backwards; that it cannot break time and time’s desire – that

is the will’s most lonely affliction.’

It may be that I’m misunderstanding Cormac McCarthy (very

likely) or that I’m misunderstanding Nietzsche (even more likely). But it may

also be, it seems to me, that McCarthy, too, is misunderstanding Nietzsche. The

result of the Nietzschean universe created in Blood Meridian appears to

be an indifference to suffering or pain or injustice. This is a simplification

of Nietzsche’s views. It is, to go back to the 9/11 example, to say that one

doesn’t care that it happened, which is not at all the same thing as saying one

accepts that it happened.

For Nietzsche, eternal return is a life-affirming belief.

Thus, to transplant it into the context of McCarthy’s The Road, say,

where life is in the process of being annihilated, is surely to go against his

thinking. In The Road we have a ‘long shear of light’, and in Blood

Meridian, ‘the evening redness in the west’. In All The Pretty Horses

we have ‘reefs of bloodred cloud’ beneath a ‘red and elliptic sun’. Further, we

are told of the ‘coloured vapours before the eyes of a divinely dissatisfied

one.’ In other words, these are the views of backworldsmen, those ‘sick and

perishing’ who, in Nietzsche’s terms:

despised the body and the earth

and invented the heavenly world, and the redeeming bloodrops… From their misery

they sought escape, and the stars were too remote for them. Then they sighed: “O

that there were heavenly paths by which to steal into another existence and

into happiness!” Then they contrived for themselves their bypaths and bloody

draughts!

And so we have our bypaths. The Road begins in a cave

before the time of man. In Blood Meridian we hear ‘cries of souls broke

through some misweave in the weft of things into the world below.’ The

Orchard Keeper’s forest ‘has about it a primordial quality, some steamy

carboniferous swamp where ancient saurians lurk in feigned sleep’. Outer

Dark’s triune ‘could have been stone figures quarried from the architecture

of an older time’. In Suttree, we are ‘come to a world within the world’

and, in The Crossing, the ancient wolves know that ‘there is no order in

the world save that which death has put there’, and ‘if men drink the blood of

God yet they do not understand the seriousness of what they do.’

All of these, it seems to me, could be part of ‘that “other

world” ... concealed from man, that dehumanised, inhuman world, which is a

celestial naught’. In other words, we are indeed in the company of Nietzsche’s

backworldsmen, those doomsayers constantly casting portents in our way,

warning, always warning, of the death to come. Zarathustra describes them thus:

Backward they always gaze toward

dark ages: then, indeed, were delusion and faith something different. Raving of

the reason was likeness to God, and doubt was sin.

Too well do I know those godlike

ones: they insist on being believed in, and that doubt is sin. Too well, also,

do I know what they themselves most believe in.

Verily, not in backworlds and

redeeming blood-drops: but in the body do they also believe most; and their own

body is for them the thing-in-itself.

But it is a sickly thing to them,

and gladly would they get out of their skin. Therefore harken they to the

preachers of death, and themselves preach backworlds.

And so, in The Road, far from experiencing an eternal

return of the soul, we find ourselves placed at the very edge of destruction,

preaching the death of everything. It is hard to know where the soul could

reside in such a landscape. Or why it would wish to do so.